Researchers reanalyzed the damage on the fragmented skull of StW-53 from Sterkfontein, which belonged to an Australopithecus or early representative of the genus Homo. They concluded that the marks previously identified on the fossil were not made by stone tools. According to a paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, they likely formed as a result of natural processes that occurred after the hominin's death.

Near Johannesburg lies a series of paleontological and archaeological sites dubbed the "Cradle of Humankind," where over many years of research, scientists have discovered numerous fossilized bones and teeth of gracile and robust australopithecines, early representatives of the genus Homo, and even the very strange hominins known as the Dinaledi people (read more about them in our article "Ten Years Later").

One of the sites located in this find-rich area is called Sterkfontein. It is a complex of limestone caves, excavations of which began in 1936. Thanks to these excavations, scientists have obtained several hundred hominin fossils, including complete skulls. For example, in 1976, the fragmented skull StW-53 was discovered there, belonging to an adult Australopithecus, Homo habilis, or another Homo species with a small brain size (approximately 450–680 cubic centimeters).

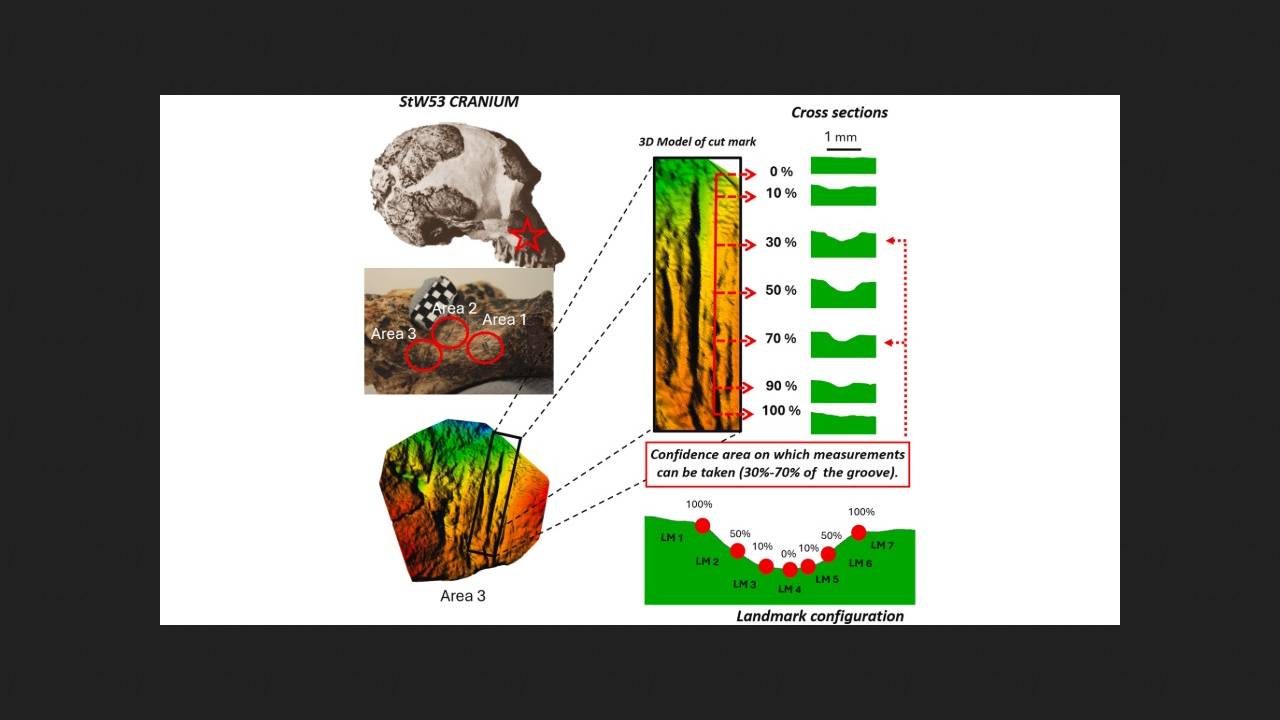

A new article by a team of scientists from the UK, Spain, the US, and South Africa devoted further research to this discovery. The team included renowned anthropologist Ronald Clarke of the University of the Witwatersrand, who had previously described a well-preserved Australopithecus skeleton nicknamed "Little Foot." This time, the scientists focused their attention on the skull StW-53, on which suspicious marks had been discovered many years earlier. For example, at the base of the zygomatic process of the upper jaw, their predecessors noticed notches that may have been made by stone tools.

One hypothesis associated with these marks was that some archaic human had severed the masseter muscle to separate the lower jaw from the skull, potentially indicating very ancient evidence of cannibalism. However, not all scientists agreed with this conclusion, suggesting that the marks on the bone could have been the result of natural processes occurring after the individual's death. This time, the researchers tested these hypotheses with an experiment, examining cut marks made on pig remains using tools made from three types of stone found at Sterkfontein.

The researchers analyzed cut marks and marks on the ancient fossil, including using machine learning. The results showed that the damage on the StW-53 skull was unlikely to be caused by human activity. According to the scientists, it likely resulted from the impact of rock fragments. Similar damage is present on the remains of the Australopithecus africanus specimen StW-498, also found in Sterkfontein.

Nevertheless, it's likely that very ancient hominins did engage in cannibalism. This is supported, in particular, by a fragment of a tibia found in the Koobi Fora region of Kenya back in 1970. This fossil, bearing traces of stone tools, is approximately 1.45 million years old.