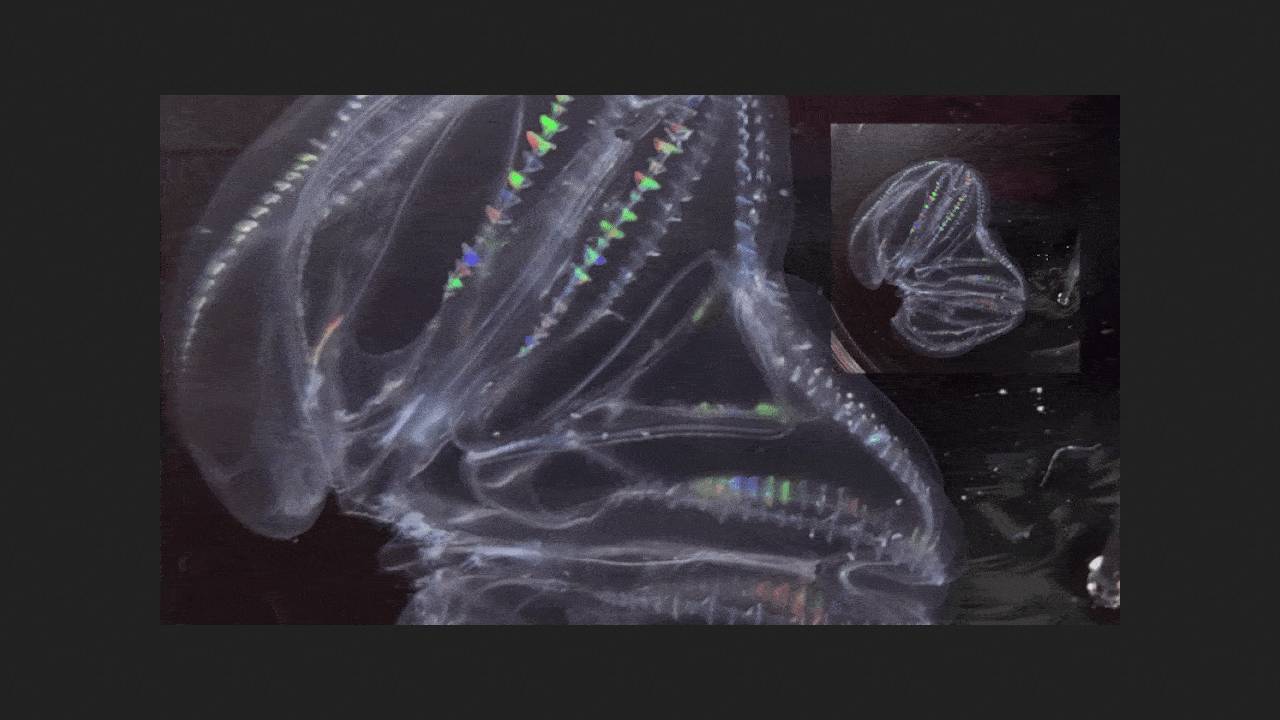

Biologists from the United States have described the fusion of two injured ctenophores into a single specimen—one with a single mouth, two aboral ends, and anus. Having noticed the fused specimens by chance, the scientists conducted experiments and induced nine pairs of ctenophores to fuse. The animals fused very quickly: after just two hours, their shared body contracted and relaxed synchronously, and the food they ingested entered both digestive systems. The results were published in Current Biology.

Mnemiopsis leidyi, a comb jellied animal, is a small, jellyfish-like creature. It lives in seawater and feeds on zooplankton. The nervous system of comb jellies is structured somewhat differently than that of most animals, and some scientists even suggest its independent origin. Their subepithelial nerve network is a syncytium—meaning neurons are connected by cytoplasmic bridges rather than synapses. Other parts of the comb jellies' nervous system contain both synapses and gap junctions, but they lack most of the neurotransmitters typical of true multicellular organisms.

Recently, researchers from the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, where a population of M. leidyi was maintained, witnessed an unusual sight. They noticed an unusually large specimen in the aquarium, with two aboral ends and two apical organs. The scientists hypothesized that this specimen was the result of a fusion of two others, which had been damaged during a recent collection and had been stored very close to each other in a small tank for some time.

Building on this observation, as well as an earlier study showing that tissue grafted from one ctenophores to another survives, scientists led by Kei Jokura conducted an experiment. They took ten pairs of ctenophores, cut off a portion of each individual's lobe (the paired body parts located near the mouth), and placed the pairs, cut-side-down, overnight.

Nine out of ten attempts were successful—the pairs of ctenophores fused. All fused specimens survived, living in the aquarium for at least another three weeks. After just one night, the border between the fused specimens became continuous, and the epithelium and mesoglea became smooth. When the scientists mechanically stimulated one lobe of the fused specimen, the entire body contracted, including the opposite lobe. The scientists concluded that the nervous systems of the ctenophores had also fused.

The researchers then decided to observe the process of fusion between the two specimens. During the first hour, the lobes of the two ctenophores relaxed and contracted asynchronously, but after two hours, their movements became synchronized. The scientists also noticed that the meridional canals—parts of the digestive system—were continuous at the point where the specimens had fused. The researchers then began feeding the fused specimens fluorescently labeled brine shrimp through one of their mouths. Food particles were detected in both digestive systems, and waste products were excreted through both anuses, at different times. Apparently, the digestive systems of the fused specimens had become linked not only physically but also functionally, while excretion control remained independent.

Since not all physiological responses were synchronized in fused ctenophores, whose neural network is primarily composed of numerous syncytial neurons, the authors hypothesized that ctenophores must also possess distinct functional neural units. Future research, the scientists believe, should focus on this issue.

The authors also concluded that M. leidyi ctenophores lack an allorecognition mechanism—meaning they likely cannot distinguish between self and non-self cells. The scientists next want to test whether individuals of different species will fuse.

Previously, scientists discovered that invasive M. leidyi actively reproduce in the northern part of its range, even when food becomes increasingly scarce, so that they can then wait out the cold period by feeding on their larvae.