German and Swedish scientists analyzed the distribution patterns of Asian mosquitoes and the viral infections they transmit in Europe and concluded that dengue and chikungunya hemorrhagic fevers could become endemic in this part of the world. Climate change plays a major role in this. A report on the study was published in the journal Lancet Planetary Health.

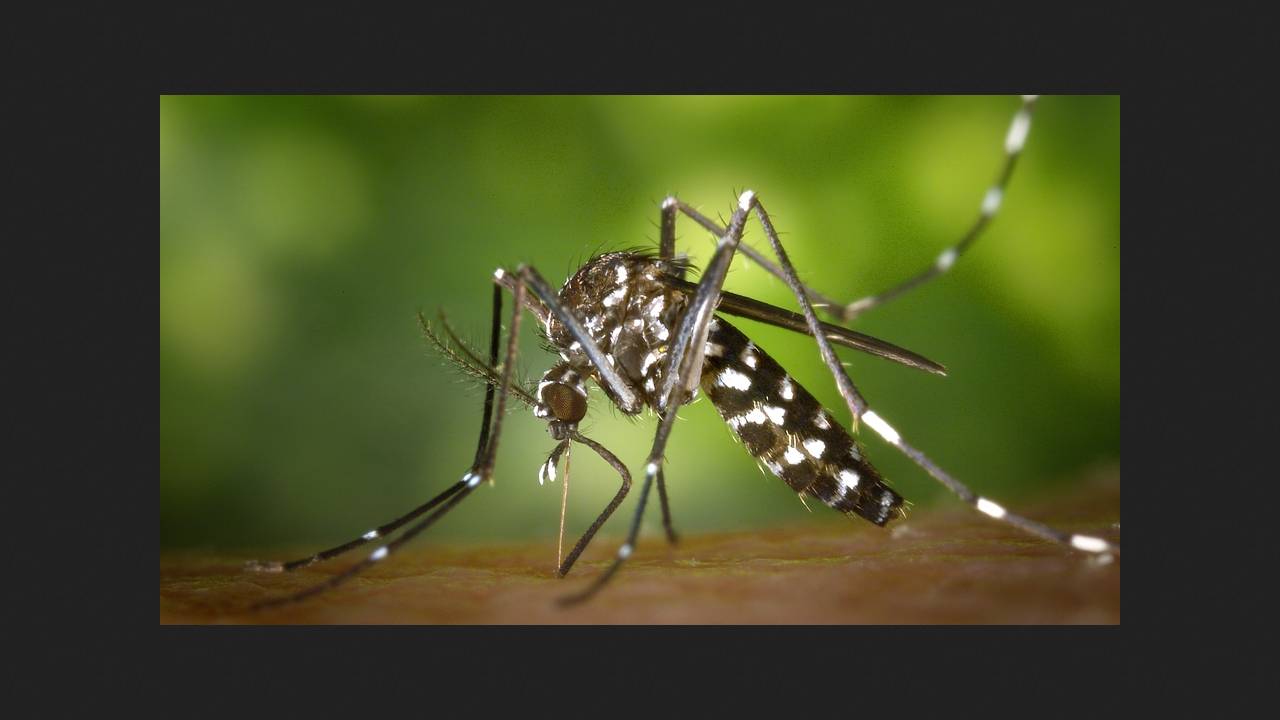

Asian tiger mosquitoes (Aedes albopictus) originate in tropical and subtropical Asian regions. Dengue and chikungunya fevers, caused by arboviruses, are endemic there, but not in Europe. Over the past half-century, Ae. albopictus has rapidly spread globally due to globalization, urbanization, trade, tourism, and climate change. In Europe, it was first discovered in Albania in 1979. In 1990, it entered Italy, and since then, it has become established in 21 countries and been introduced to six more. In its European habitats, this mosquito can transmit arboviruses during imported cases of the disease, causing localized outbreaks. The first such autochthonous outbreak of chikungunya fever in Europe, with 330 cases, occurred in Italy in 2007. Similar outbreaks have now been reported in four European countries.

Jan Semenza of Umeå University and Heidelberg University and colleagues conducted a systematic review of reports from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control and the World Health Organization, technical reports and surveillance data, as well as peer-reviewed publications from PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases from January 1990 to October 2024, in search of information on the spread of Ae. albopictus and outbreaks of dengue and chikungunya. These data were used in a time-to-event analysis to track the period from the establishment of the vector insect in a locality to the occurrence of autochthonous outbreaks of infections in NUTS 3 regions.

The analysis was conducted using single- and multivariable regression, accounting for land use types, demographic and socioeconomic factors, imported cases, and climate variables. We also analyzed recurring outbreaks, stratified them by warm and cold regions based on average summer temperatures below and above 20 degrees Celsius, and projected outbreak risks from the 2030s to 2060s under different climate change scenarios.

It was found that from 1990 to 2024, the interval between the first establishment of Ae. albopictus in NUTS 3 regions and the first outbreak of dengue or chikungunya fever decreased from 25 to less than five years. Over the same period, the interval between the first and second outbreaks in the region decreased from 12 years to less than a year. Regression analysis showed that favorable climatic conditions play a significant role in this process. Each degree Celsius increase in average summer temperature was associated with an outbreak odds ratio of 1.55 (p < 0.0001) after adjusting for health funding, imported cases, and land use type. First outbreaks occurred more frequently in warm regions than in cold ones (log-rank p = 0.088). The situation is expected to worsen significantly with increasing climate change: under the highest greenhouse gas emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5), the number of dengue and chikungunya fever outbreaks in Europe is projected to increase almost fivefold by 2060 compared to the 1990-2024 level. The authors conclude that these results highlight the need for significant mosquito control measures, enhanced surveillance, and early warning systems for outbreaks to prepare for the growing risk of Ae. albopictus-borne diseases becoming endemic in the European region. Previously, American scientists conducted an empirical systematic study that found that global climate change, associated with greenhouse gas emissions, increases the incidence of 58 percent of infectious diseases to some degree, while decreasing it for only 16 percent.