Paleogeneticists analyzed more than 400 ancient human genomes to determine how the population that left behind the Yamnaya culture formed. The scientists concluded that approximately 80 percent of the Yamnaya's ancestors descended from groups genetically similar to people who inhabited the steppe zone from the Lower Volga region to the lands north of the Caucasus Mountains during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Ages. They likely interbred with descendants of Ukrainian hunter-gatherers of the Neolithic era in the area between the Dnieper and Don rivers, forming the Sredny Stog culture. As reported in a paper published in the journal Nature, the processes occurring in these lands resulted in the emergence of a population around 4000 BC that, several centuries later, rapidly expanded in size and widely disseminated the Yamnaya culture.

About ten years ago, paleogeneticists discovered that around five thousand years ago, the gene pool of ancient European populations began to change significantly due to a significant influx of new people originating from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, where the Yamnaya culture then existed. During this period, the Yamnaya actively colonized new lands, and individual groups migrated even as far east as the Altai Mountains and the Minusinsk Basin. This expansion also occurred westward, toward Southeastern and Central Europe, and its consequences are clearly visible in the modern genetic landscape of Europe.

The massive gene flow from the steppe in the Early Bronze Age, unknown to scientists until ancient DNA analysis, has reignited the debate regarding the original homeland of the Indo-European languages. Proponents of the so-called steppe hypothesis suggest that the migrations of the Yamnaya and their descendants facilitated the spread of the languages of this vast family from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, which are now spoken by over 40 percent of the world's population. It is therefore not surprising that the Yamnaya culture, their origins, and their legacy have received considerable attention in recent years from leading laboratories and researchers.

До сих пор происхождение самих ямников оставалось не очень понятным. Чтобы прояснить этот вопрос, большой научный коллектив во главе с Роном Пинхаси (Ron Pinhasi) из Венского университета и Дэвидом Райхом (David Reich) из Гарвардского университета представил результаты дальнейших генетических исследований этого вопроса. В своей работе ученые сосредоточили внимание на анализе 428 древних геномов, 299 из которых они опубликовали впервые. Останки, из которых секвенировали ДНК, принадлежали людям, которые жили между 6400 и 2000 годами до нашей эры, причем подавляющее большинство из них раскопали на территории современной России. Основная часть проанализированных последовательностей представляла собой геномы людей эпох энеолита и ранней бронзы из степной зоны Восточной Европы, в том числе геномы значительного количества представителей ямной археологической культуры.

В своей статье ученые описали три так называемых клины — постепенных перехода от одной популяции к другой между двумя крайними вариантами — для энеолита и раннего бронзового века степной зоны Восточной Европы: волжскую, днепровскую и нижневолжско-кавказскую. В этой модели «ядро» (большинство геномов с хорошим покрытием) ямников входит в днепровскую клину, но при этом располагается на ее краю.

Новые данные, по словам ученых, противоречат недавно предложенной модели, согласно которой популяция ямников возникла в результате смешения охотников-собирателей со Среднего Дона и потомков кавказских-охотников собирателей. Райх и его коллеги пишут, что в генофонде этих двух предложенных предковых популяций отсутствовали два компонента, которые были у ямников. Один из них характерен для неолитических популяций Анатолии, а другой — для древних жителей Сибири и Центральной Азии, восходящий к сибирякам эпохи верхнего палеолита (так называемым древним северным евразийцам). Последний компонент присутствовал в эпоху энеолита у некоторых групп, проживавших в Нижнем Поволжье и к северу от Кавказских гор, которых ученые отнесли к кластеру Бережновка-II — Прогресс-II (в легендах к изображениям он обозначен BPgroup), названному по одноименным памятникам.

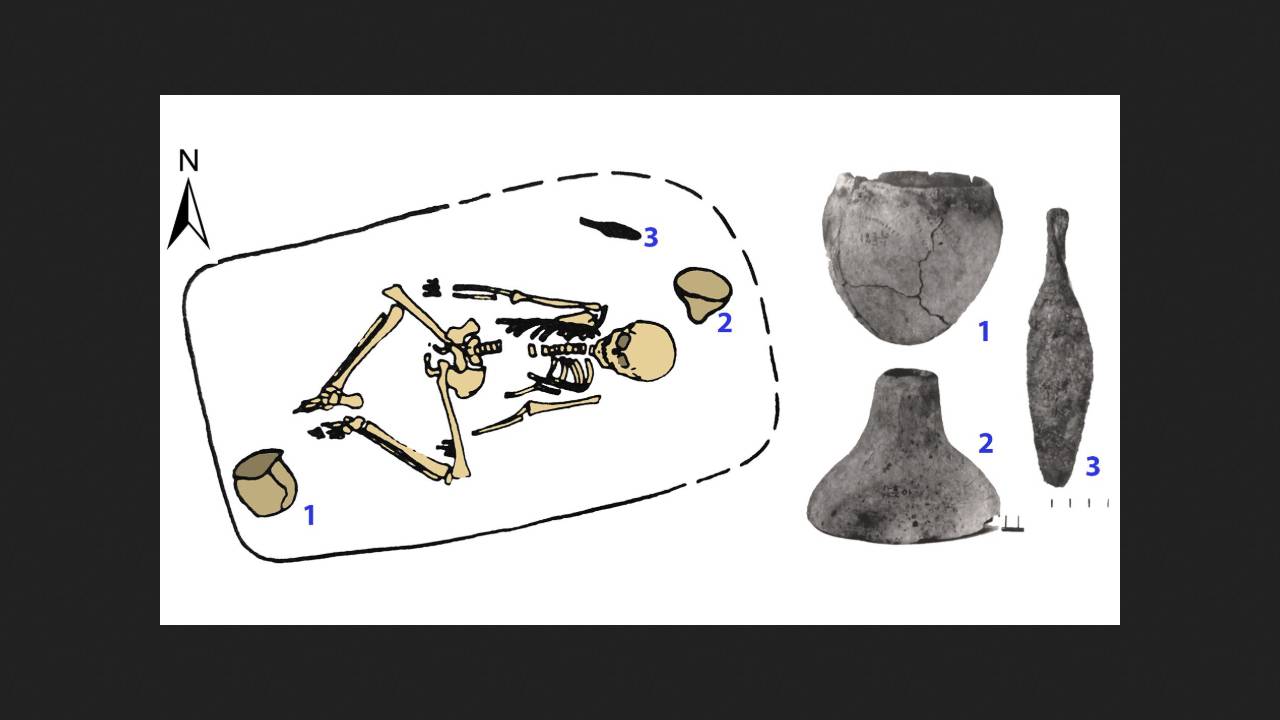

Происхождение «ядра» ямников, по данным исследователей, можно смоделировать из двух популяций, представленных в выборке. Одна из них представляет собой часть представителей среднестоговской культуры. А другая — двух людей из захоронений эпохи энеолита (около 4150–3600 годов до нашей эры), раскопанных в могильниках неподалеку от села Ремонтное в Ростовской области. Геномы этих людей относятся к так называемой нижневолжско-кавказской клине, а среди их предков, по всей видимости, были люди как с северным происхождением (на эту роль подходят индивиды из кластера Бережновка-II — Прогресс-II), так и с южным, связанным с кавказскими популяциями эпохи неолита.

The scientists concluded that the origin of the Yamnaya core is best understood as the result of admixture between groups belonging to the Lower Volga-Caucasian cline (approximately 80 percent of the gene pool) and populations from the Dnieper-Don interfluve, which had a significant number of ancestors descended from Ukrainian hunter-gatherers of the Neolithic era. Furthermore, groups from the Lower Volga-Caucasian cline also provide the missing components in the model, linked to Neolithic populations from Anatolia and ancient populations of Siberia and Central Asia.

In addition to the origins of the Yamnaya, the researchers also analyzed the genomes of ancient people from Transcaucasia and Asia Minor. They discovered that as early as 4000 BC, the gene pool of people living in what is now Armenia contained a significant contribution from groups belonging to the Lower Volga-Caucasian cline. This, according to the researchers, indicates their southward migration, where they interbred with the local population. Furthermore, contributions from these groups are also found in later populations that lived in Asia Minor during the Bronze Age. Ultimately, the scientists see this as confirmation of the hypothesis that Indo-European languages, including those belonging to the Anatolian branch, may have arrived in this region with migrants from beyond the Caucasus Mountains.

N + 1 reported on other studies related to the Yamnaya culture. For example, scientists discovered a genetic predisposition to multiple sclerosis. Moreover, gene variants that increase the risk of developing this disease have been preserved in the gene pool of modern Europeans.