American and Canadian scientists used event-based analysis to find that limiting sugar consumption in the first 1,000 days after conception significantly reduces the risk of developing serious chronic diseases later in life. The study was published in the journal Science.

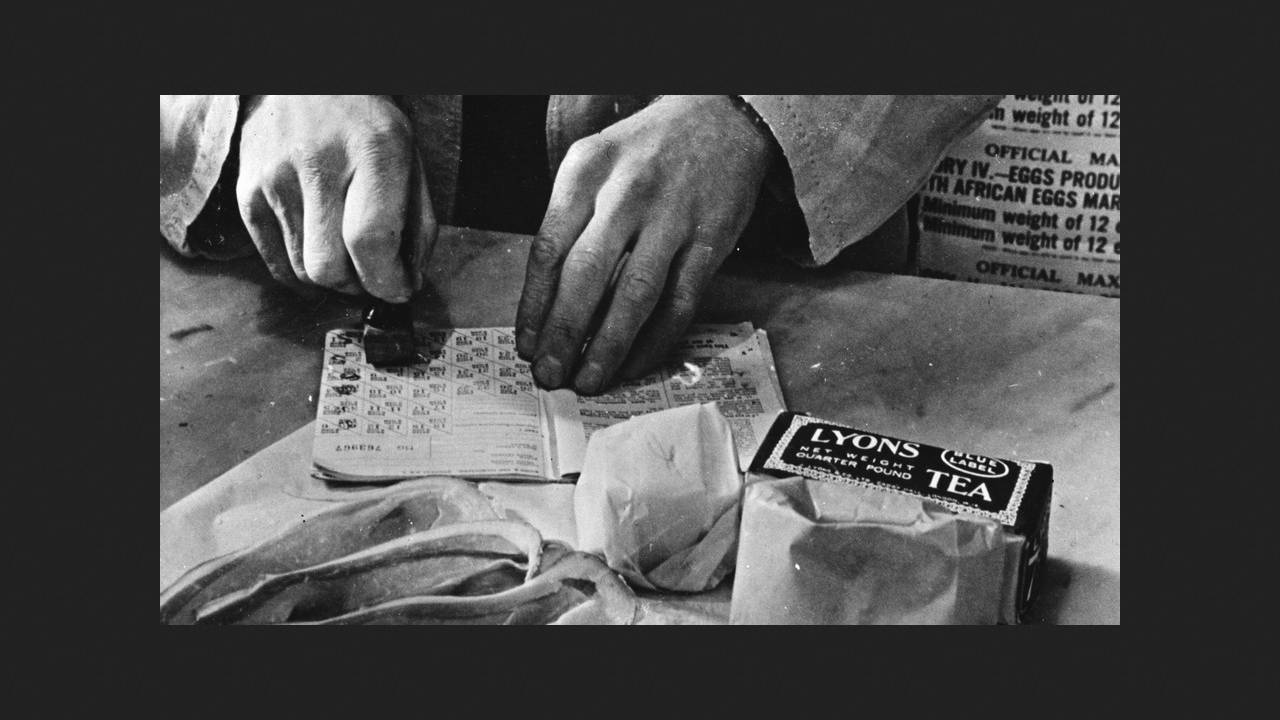

During World War II, rationing of various foodstuffs was introduced in Great Britain. This continued until 1953, affecting sugar and sweets. The restrictions during this period were comparable to modern dietary recommendations for sugar consumption: less than 40 grams per day for adults, less than 15 grams for children, and no sugar at all for children under two. After the abolition of sugar and sweets coupons, the average adult's consumption almost immediately doubled: from 41 grams per day in the first quarter of 1953 to 80 grams per day in the third quarter of 1954. Similar trends were observed among children. Thus, the country created a generation that was virtually deprived of sugar in its early childhood, including limited maternal sugar intake during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Tadeja Gracner of the University of Southern California and colleagues took advantage of this natural quasi-experiment. They analyzed data from over 60,000 British adults born between October 1951 and March 1956 from the UK BioBank repository, who were aged 51–66 at the time of the survey. More than 38,000 of these individuals were conceived 1,000 or more days before October 1953 and were included in the cohort exposed to sugar rationing; the remaining 22,000-plus were born later and were considered unexposed. Gender and ethnic composition, as well as family history of diabetes and cardiovascular disease, as well as the estimated genetic risk for obesity, were comparable across these cohorts.

By the time of inclusion, almost 4,000 participants were diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, and more than 19,600 had arterial hypertension. The risk of these diseases increased with age in both cohorts; however, in those exposed to rationing, they developed less frequently and at a later age. In particular, the hazard ratio (HR) for developing diabetes mellitus in those affected by rationing only in the prenatal period and in the prenatal period plus the first one or two years of life, compared with unaffected ones, was 0.87; 0.75 and 0.64, and it occurred in the case of development 1.46; 2.80 and 4.17 years later. For arterial hypertension, these indicators were HR of 0.92; 0.85 and 0.81 and 0.53; 1.47 and 2.12 years, respectively (all indicators are statistically significant, for most p < 0.001). Thus, limiting sugar consumption during pregnancy and breastfeeding, as well as during the first two years of a child's life, may be an effective method for preventing the development of diabetes and hypertension later in life, the authors conclude. Previously, Chinese researchers demonstrated statistically that drinking beverages with sugar or artificial sweeteners is associated with an increased risk of atrial fibrillation, while their French colleagues linked the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juices to an increased risk of cancer. Meanwhile, an analysis of a prospective cohort of Danes found no increased risk of diabetes or death associated with adding sugar to tea or coffee.