American surgeons performed the world's first bladder transplant from a deceased donor. He also underwent a kidney transplant, according to the University of California, Los Angeles press service.

In cases of cancer, severe infections, and other terminal bladder dysfunctions, the bladder must be removed. To ensure urine flow from the ureters to the bladder bag, patients typically have an artificial reservoir created from a section of intestine. Because this tissue is poorly suited for such functions, up to 80 percent of patients subsequently experience complications such as recurrent infections, kidney dysfunction, and digestive problems.

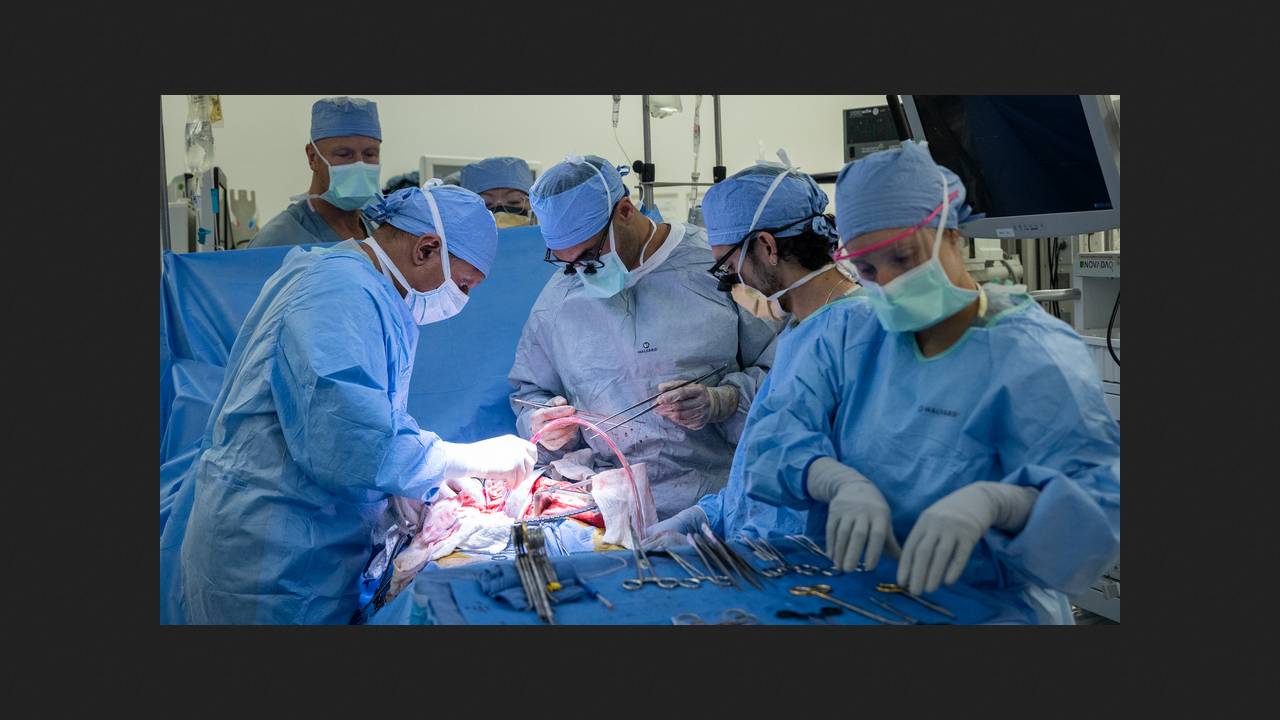

To help such patients, urologists Inderbir Gill and Nima Nassiri began developing a donor bladder transplant more than four years ago at the University of Southern California. This procedure is technically challenging due to the complex blood supply to the pelvic organs. The doctors developed the technique first on pigs, then on human cadavers and brain-dead donors, continuing this work after moving to the University of California, Los Angeles. During their experiments, they decided to connect the right and left arteries and veins of the donor bladder to reduce the number of vessels to be sutured during the surgery.

The first organ recipient was 41-year-old Oscar Larrainzar, whose bladder was removed due to a rare tumor—urethral adenocarcinoma—leaving only a bladder fragment, approximately 30 milliliters in volume. Shortly thereafter, both his kidneys were also removed due to cancer and end-stage renal failure. Bladder reconstruction using a piece of intestine was impossible due to numerous post-operative scars in the abdominal cavity. The patient had been on dialysis for seven years, but its effectiveness began to rapidly decline, and severe edema developed.

Когда 4 мая нашелся подходящий донор, Гилл и Нассири приняли участие в извлечении почки и мочевого пузыря для пересадки. Их в тот же день пересадили Ларраинзару по разработанной экспериментальной технологии. Операция продлилась примерно восемь часов. Почка стала сразу вырабатывать большой объем мочи, которая беспрепятственно поступала в мочевой пузырь, и состояние пациента стало улучшаться. После операции диализ ему не понадобился, уровень креатинина в крови стал быстро снижаться. В течение послеоперационной реабилитации масса его тела снизилась на девять килограмм за счет выведения избыточной жидкости. Через девять дней после операции мужчину выписали домой.

Поскольку у пересаженного мочевого пузыря отсутствовала иннервация, врачи не рассчитывали, что пациент сможет ощущать его наполнение, и рассматривали использование катетеров, манипуляций с брюшной стенкой и электростимуляцию органа для обеспечения оттока мочи. Однако, когда на приеме через два дня после выписки Нассири извлек катетер и предложил Ларраинзару выпить воды, тот сообщил, что хочет и, по ощущениям, может помочиться. К удивлению урологов, он начал делать это самостоятельно. Тем не менее пока неясно, как будут обстоять дела с мочеиспусканием в долгосрочной перспективе, и какой объем иммуносупрессии понадобится пациенту.

Экспериментальную операцию провели в рамках инициированных Гиллом и Нассири пилотных клинических испытаний, в которых планируется участие пяти человек. Поскольку пока сложно взвесить потенциальную пользу донорского мочевого пузыря и риск, связанный с иммуносупрессивной терапией, пока вмешательство рассматривают в первую очередь как средство помощи пациентам, и без этого нуждающимся в иммуносупрессии из-за пересадки другого органа.

Необходимые многим урологическим пациентам стенты и катетеры мочевыводящих путей приходится часто менять из-за отложения на их стенках корки солей и формирования бактериальных биопленок. Швейцарские и американские исследователи разработали технологию самоочистки таких устройств с помощью напоминающих мерцательный эпителий биомиметических ресничек, которые активируются ультразвуком.