US researchers examined data on 77 hockey players who donated their brains after death and found that each additional year of hockey playing increased the risk of chronic traumatic encephalopathy and the level of phosphorylated tau protein in the brain. This is the first and largest study of the link between hockey playing and the development of the disease. The results were published in JAMA Network Open.

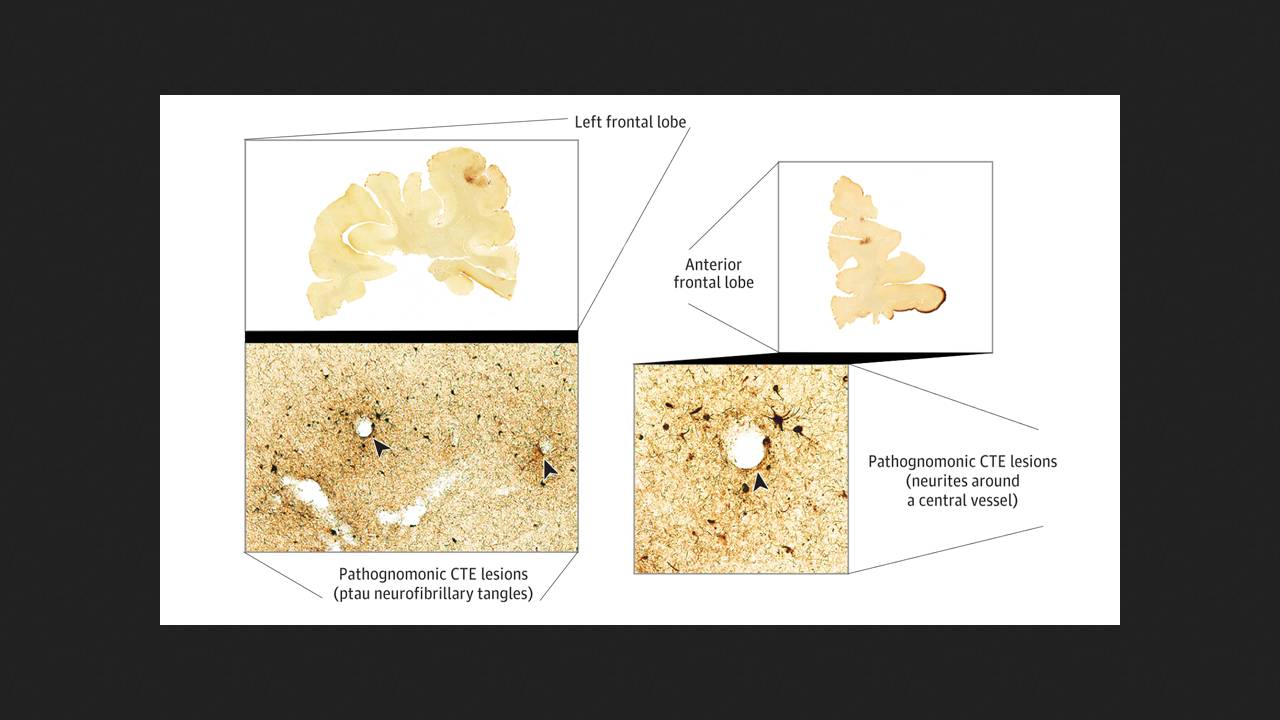

"Boxer's dementia," or chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), is a neurodegenerative disease caused by repeated head injuries. Physiologically, it is characterized by excessive accumulation of phosphorylated tau protein in the brain, similar to Alzheimer's disease, and symptoms include cognitive impairment, depression, and suicidal behavior. CTE is common among boxers and American football players. An early study showed that the risk of developing the disease increases with each year of play. This is likely also true for ice hockey, where players also frequently suffer head injuries, but this connection has not been previously studied.

Scientists from the Boston University School of Medicine and other US institutions, led by Bobak Abdolmohammadi, analyzed data from 77 male hockey players who donated their brains to three brain banks after their deaths. CTE was detected in 42 of the 77 donors (54.5 percent), while 27 of the 28 professional players (96.4 percent) suffered from the disease.

The risk of developing the disease increased with playing time. Only 5 of 26 men who played hockey for less than 13 years developed CTE. Among donors who played for more than 23 years, almost 96 percent—23 out of 24—suffered from the condition. Even after accounting for all other factors—age at death, participation in other contact sports, age at which hockey began, player position, and number of concussions—each year of playing increased the risk by 1.34 times. Furthermore, the load of phosphorylated tau protein in the brain increased with playing time.

The majority of donors participating in the study committed suicide: ten people, or 38.5 percent, of those with CTE and ten donors, or 28.6 percent, of those without. A similar pattern is also observed among American football players suffering from the same condition.

The authors identified cutoff values for playing time: 7.5 and 18 years. Men with less than 7.5 years of playing experience generally did not suffer from CTE, while those with more than 18 years did. However, the scientists noted that the sample was not representative, meaning the observed CTE incidence cannot be considered representative of the CTE incidence in the population of male hockey players. Furthermore, this study, like studies with American football players, used years of playing as the primary indicator, which does not always directly correlate with the incidence of head injuries.

We discussed chronic traumatic encephalopathy in more detail in the article "Amazing Football."