Paleogeneticists analyzed the DNA of 46 individuals whose remains were excavated from several ancient burial sites in the Baikal region. The scientists discovered that more than five thousand years ago, local hunter-gatherers suffered from plague outbreaks, with the disease apparently posing the greatest threat to children and adolescents at the time. This was reported in a preprint posted on bioRxiv.org.

Genetic studies in recent years have shown that people suffered from the plague long before the first recorded pandemics. Scientists have already discovered several cases of ancient people contracting this infection more than five thousand years ago. For example, Yersinia pestis DNA was isolated from the remains of people who lived approximately 5,700–5,300 years ago in the western part of modern-day Russia, Central Asia, and the Lake Baikal region.

Furthermore, in recent studies, paleogeneticists have described several cases of plague infection among ancient inhabitants of the Baltics and Scandinavia. For example, a couple of years ago, scientists discovered Yersinia plague DNA in the remains of a hunter-gatherer who died in what is now Latvia approximately 5,300–5,050 years ago. More recently, researchers identified cases of comparable age in Germany and Scandinavia, and in the latter, they found evidence that the plague already had epidemic potential.

Scientists from the UK, Denmark, Canada, Russia, and the US, led by renowned paleogeneticist Eske Willerslev, have returned to studying the remains of ancient hunter-gatherers who lived in Siberia. They sequenced DNA from the bones and teeth of 46 Neolithic individuals whose burials were excavated at four burial grounds in the Baikal (Angara) region: Shumilikha (5,580–5,320 years ago), Ust-Ida-I (5,600–5,320 years ago), Bratsky Kamen (5,475–5,052 years ago), and Serovo (5,290–4,870 years ago).

The researchers first noted that they had discovered relatively long, common ancestry linkage blocks in the genomes of hunter-gatherers buried approximately 340 kilometers apart. This suggests a close relationship between these individuals and also suggests that the ancient population of the Angara region was quite mobile. Furthermore, the scientists discovered that these individuals' genomes lacked extensive regions of homozygosity, indicating that they avoided inbreeding. Based on this finding, the researchers estimated the effective population size of the local hunter-gatherers at approximately 18,219 individuals (9,445–42,062 individuals at a 95 percent confidence interval).

Scientists discovered that one of the individuals buried at the Ust-Ida-I burial ground suffered from brucellosis. They also identified Yersinia plague DNA in the remains of 18 other individuals. The largest number of samples came from the Ust-Ida-I site, where the pathogen's genetic material was found in 12 of the 31 skeletons studied. One case each was found at the Shumilikha and Serovo burial grounds, and the remaining four were found at the Bratsky Kamen burial ground.

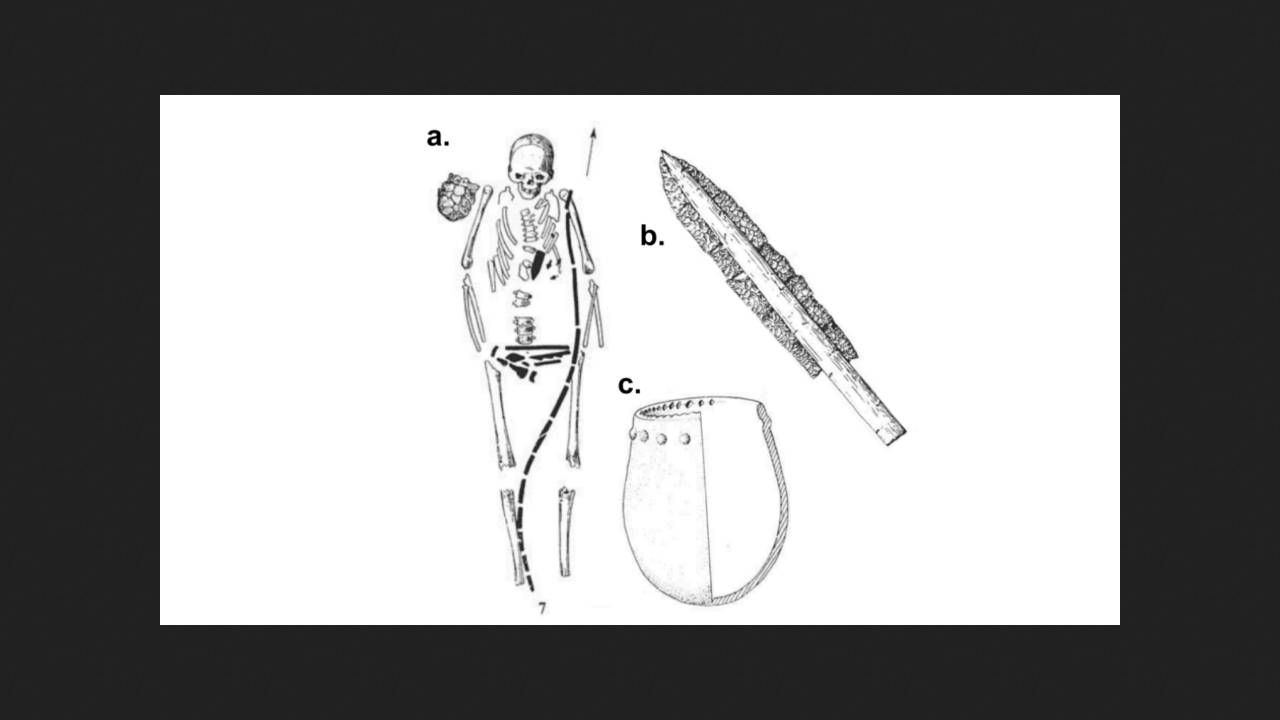

A detailed analysis of remains from the aforementioned sites indicated that plague was likely already causing outbreaks at that time. Moreover, the disease likely posed the greatest threat to children and adolescents. For example, a study of materials from the Ust-Ida-I and Bratsky Kamen burial grounds revealed that the peak mortality rate occurred among children aged 7.5 to 11 years. Moreover, the burial grounds contained burials containing the remains of children, likely related. For example, at the Bratsky Kamen site, archaeologists excavated a triple burial of plague-infected girls aged four to nine years. Two of the girls were third-degree relatives (likely first cousins), and the third was possibly related to them through their mother's line (the preservation of her DNA was poor, so this cannot be determined with certainty).

Among other things, the researchers also revised the divergence time of Yersinia pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis bacteria. According to the new estimates, their evolutionary lineages diverged approximately 9,317 years ago (7,289–11,344 at a 95 percent confidence interval), that is, earlier than previously thought.

Paleogeneticists have discovered the plague bacillus not only in the remains of ancient humans. For example, scientists recently isolated the DNA of this pathogen from the bones of a dog that lived on the island of Gotland approximately 4,900–4,500 years ago.