American researchers have transplanted a patient's own immature germline stem cells, harvested as a child before undergoing chemotherapy that rendered him sterile, into his testicle for the first time. Whether he has since begun producing sperm remains unclear. A description of the technique is available on medRXiv.org, and the patient's story was reported by the AP news agency.

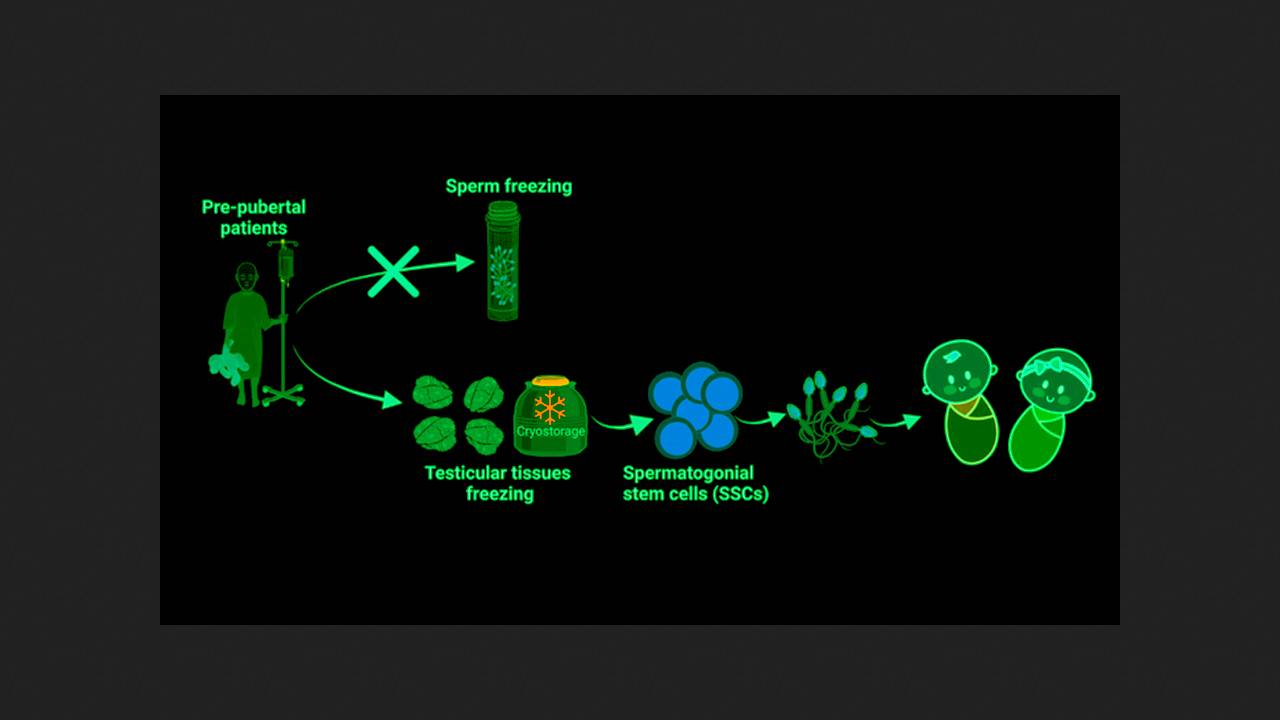

Thanks to modern medicine, up to 85 percent of children with cancer survive to adulthood without relapse. However, approximately one in three of them remains infertile as a result of chemotherapy, as actively dividing germline stem cells, which give rise to gametes (sperm and eggs), are sensitive to it. To enable cancer patients to have children in the future, cryopreservation of mature sperm or eggs is currently offered, but these are not produced before puberty.

Kyle Orwig's laboratory at the University of Pittsburgh has been developing cryopreservation and subsequent replantation of germline stem cells (gametogonia) for many years. After achieving positive results in monkey experiments, the researchers began preserving stem cells collected by needle biopsy from prepubertal children with cancer before chemotherapy. Since 2011, the laboratory has been storing purified cell cultures from approximately 1,000 boys for clinical trials.

One of them was Jaiwen Hsu, who was diagnosed with bone cancer at age 11 and began chemotherapy. His parents contacted the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and enrolled him in the stem cell cryopreservation program. More than 10 years later, he became the first patient with preserved cells to request a transplant – a sperm analysis revealed predictable azoospermia (the absence of living sperm in the ejaculate). He had no plans to start a family at the time, but he wanted to see if the experiment would be successful.

In 2023, as part of a separate clinical trial, Oruig and his colleagues performed an autologous transplant of a patient's testicular cell suspension containing spermatogonia. To do this, the researchers used a technology they had developed and tested on animals. Under ultrasound guidance, they inserted a needle through the base of the scrotum into the rete testis (the Hallerian network)—which connects to all the seminiferous tubules where sperm production occurs—and used this needle to precisely deliver stem cells.

The procedure went without complications, and a subsequent ultrasound revealed normal testicular tissue structure. The patient's testosterone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and luteinizing hormone levels were normal, but inhibin B (a marker of spermatogenesis) was low. A semen analysis one year after the transplant continued to show azoospermia. Oruig believes it's too early to draw conclusions—in monkey experiments, only small amounts of sperm were recovered by aspiration, but they were successfully used for conception through in vitro fertilization. Xu, now 26, noted that regardless of the results, he is pleased to have participated in the development of the technology and is grateful to his parents for including him in this program.

In parallel with the preservation of germline stem cells, experiments are underway to cryopreserve intact fragments of testicular tissue. In January 2025, Ellen Goossens and colleagues from the Free University of Brussels implanted such a fragment of a patient's own tissue for the first time. It was harvested before chemotherapy at age 10 and stored for 16 years. It is also too early to evaluate the results of this experiment.