Scientists from Israel discovered that people with congenital anosmia (lack of smell) and people with a normal sense of smell breathe differently. People without anosmia had twice as many peaks in breath flow per breath, apparently because they detected specific odors. People with anosmia also had more frequent pauses during inspiration and a lower peak expiratory flow rate while awake. Based on these breathing patterns, the researchers were able to determine whether a patient had congenital anosmia with 83 percent accuracy. The study was published in Nature Communications.

Anosmia, or loss of smell, isn't limited to a lack of odors: patients with anosmia are more susceptible to depression and often complain of emotional blunting and a feeling of isolation. Acquired anosmia (due, for example, to viral infections, nasal diseases, or head injuries) is associated with a threefold increased risk of death within five years. It's not entirely clear how exactly the loss of smell—or its absence from birth—leads to these effects. One hypothesis is that anosmia also alters breathing.

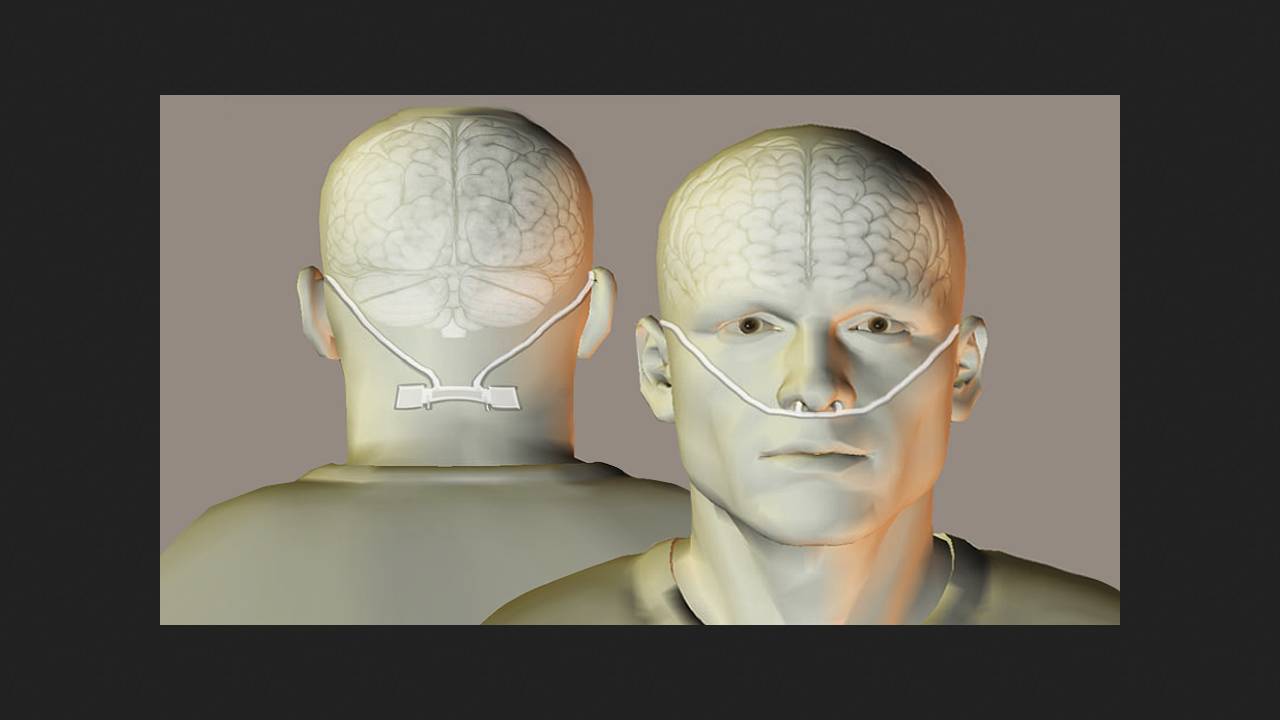

Researchers from the Weizmann Institute of Science, led by Noam Sobel, decided to compare the breathing patterns of people with and without anosmia. To analyze nasal breathing, they used a device they had previously developed that measures pressure in the nostrils. In the first experiment, 21 people with congenital anosmia and 31 people without it wore the device throughout the day—while awake and asleep. Participants were asked to maintain their daily routine and keep an activity diary.

The respiratory rates of normosmia and anosmia participants were approximately the same both while awake and while sleeping. All subjects breathed less frequently while sleeping. However, a more detailed analysis of nasal airflow revealed that a single breath in normosmia often contained several peaks, while in anosmia patients, only one. Over the course of an hour, this difference reached 240 peaks, resulting in significant differences in respiratory parameters. However, this difference was significant only during wakefulness; it decreased during sleep. The scientists hypothesized that this is related to odors that people without anosmia involuntarily detect.

To test this, the scientists conducted another experiment: people with normosmia were placed individually in a room devoid of all odors. In this case, the average number of respiratory peaks per minute was slightly lower than in people with anosmia while awake (17.2 ± 3.3 versus 19.5 ± 5.8). Thus, the scientists' hypothesis was confirmed. However, this test had limitations: the people in the room were sitting still, which could have affected their breathing.

The researchers then examined a number of other nasal airflow parameters and discovered several more differences that persisted during sleep. Patients with anosmia were more likely to pause during inhalation (81 percent versus 75 percent of breaths with pauses). They also had a decreased peak expiratory flow rate while awake, and a parameter related to inhalation volume changed during sleep.

In conclusion, the scientists demonstrated that, based on these breathing parameters, the classifier could detect the presence of anosmia with up to 83 percent accuracy. Specifically, it classified anosmic breathing as anosmic with 67 percent accuracy, and normosmic breathing as normosmic with 94 percent accuracy. The classifier's accuracy was independent of the average number of respiratory peaks per minute, as excluding this parameter still yielded 81 percent accuracy.

This study did not include patients with acquired anosmia, so the results do not shed light on whether similar changes occur with olfactory loss over life, and if so, how quickly. However, this work does demonstrate that people with congenital anosmia and those with normosmia breathe differently. The authors suggest that these effects may partially explain the adverse lifespan health consequences associated with anosmia.

Previously, scientists found that loss of smell due to head injury is associated with more severe symptoms of depression and sexual dissatisfaction.