Scientists from the United States have discovered that young children are able to (at least briefly) remember visual stimuli—a process accompanied by activity in hippocampal neurons. Thus, the cause of infantile amnesia likely lies not in the inability of the immature hippocampus to encode memories, but rather in the inability of these memories to be retrieved. The study was published in the journal Science.

People typically don't remember what happened to them in early childhood. This phenomenon is called infantile amnesia and is also characteristic of many other mammals, but the mechanism behind it hasn't been fully elucidated. All theories and explanations boil down to three: the child's brain is unable to form episodic memories (that is, encode them); memories are formed but not retained into adulthood; or memories are formed and retained, but access to them is lost (the retrieval process is impaired).

The latter theory is supported by studies in rodents, who can recall forgotten infant memories by placing them in the same context or by optogenetically activating hippocampal neurons that were active during the memorization process. Human infants are also capable of memorizing general patterns as early as three months—this learning depends on the hippocampus. However, the encoding of episodic memories depends on the trisynaptic circuit in the hippocampus, whereas the memorization of general patterns relies on the monosynaptic pathway, which develops earlier. Thus, the question of when the infant hippocampus begins encoding episodic memories remains open.

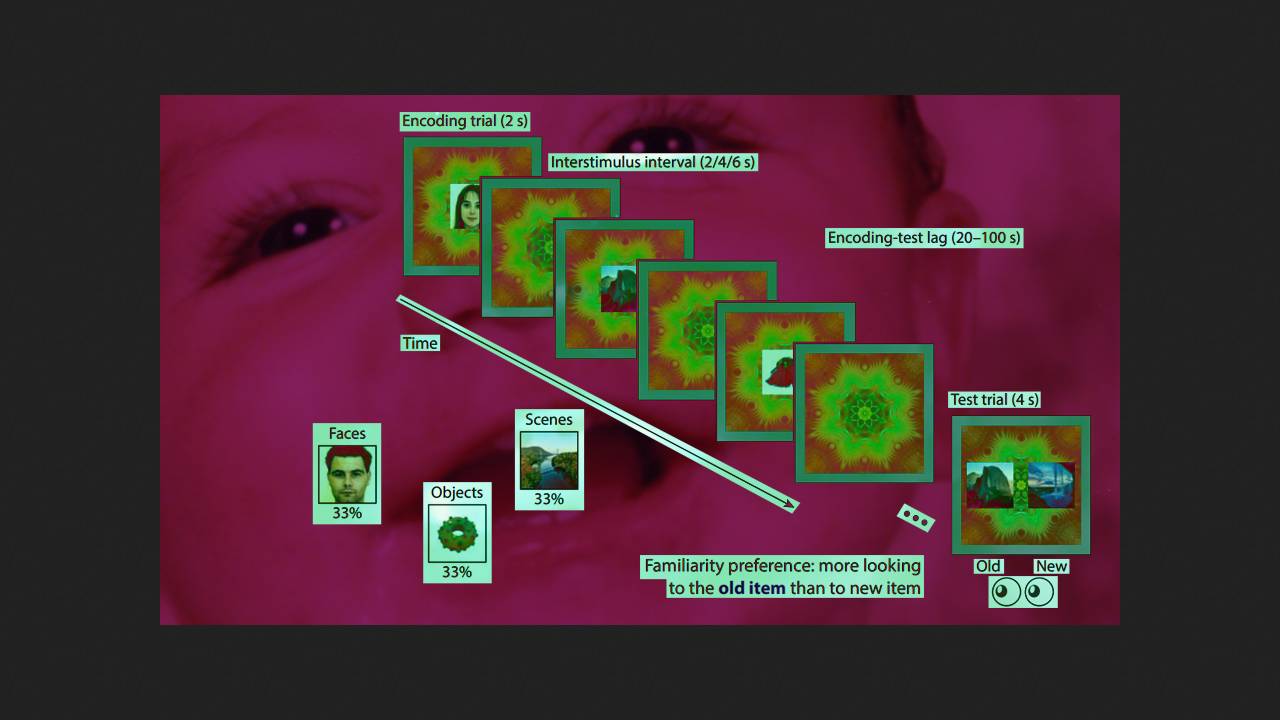

Tristan Yates of Columbia University and his colleagues from various universities in New York conducted an experiment with 26 infants aged four months to two years. Half the children were over a year old, and half were younger. They were placed in an fMRI scanner and shown images of objects, faces, and landscapes. Periodically, instead of a new image, a pair of images appeared on the screen—one seen 20-100 seconds earlier and another new one. If the child looked longer at the familiar image, the scientists concluded that they had remembered it. Simultaneously, the researchers recorded brain activity to assess the involvement of the hippocampus in memory.

Overall, the scientists found no significant preference for familiar images across the entire sample. However, some children recognized previously seen images throughout the experiment. In these cases, hippocampal activity during the first image presentation was significantly higher, particularly in the posterior hippocampus, which in adults is responsible for encoding episodic memories. This effect was observed primarily in children over one year old, although children of all ages paid equal attention to the stimuli. Furthermore, older children also showed additional activation of the orbitofrontal cortex during memorization. The effect was also stronger when there was a shorter time lapse between the first and second image presentations.

Since a preference for familiar objects is traditionally associated with incomplete encoding, these results may reflect the still-developing function of the hippocampus. However, they do indicate that the hippocampus of children as young as twelve months can encode memories. This means that infantile amnesia is likely explained by failures in memory storage or retrieval.

The method used did not allow the scientists to assess the neural mechanisms of memory retrieval, as the children were shown two images at once—a familiar one and a new one—in the test trials. Future studies could test other schemes in which only one object is presented, as well as other forms of memory, such as free recall or associative inference.

Previously, scientists discovered that the hippocampus of two-year-old children responds to familiar songs, even while they are sleeping.