Paleogeneticists analyzed the DNA of two newborn children whose remains were found during excavations at the Western Hill of Çatalhöyük. The scientists concluded that these children, who lived in the early sixth millennium BCE, were not closely related, despite being buried under the floor of the same house. A preprint of the study is available on bioRxiv.org.

In the Turkish province of Konya lies one of the most famous archaeological sites dating back to the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods—Çatalhöyük. It has survived to this day as two mounds (Eastern and Western), which contain the multi-layered remains of settlements that existed between 7100 and 5600 BC. Over the course of many years of excavations, beginning in the middle of the last century, archaeologists have uncovered the ruins of numerous houses built of mud brick and wood, the walls and floors of which were adorned with paintings and carved images. The remains of the settlement's many inhabitants were often buried beneath the floors and platforms of these structures (read more about it in the article "The Mistress of the Double Mountain").

In recent years, the remains of people from Çatalhöyük have occasionally become the subject of paleogenetic research. However, scientists have primarily focused on the bones and teeth found in the older Eastern Hill. Now, Ayça Doğu of the Middle East Technical University has presented the results of DNA analysis of two individuals from the Western Hill, where, during excavations of a structure, archaeologists discovered the remains of two newborn children who lived between 6000 and 5700 BC, that is, during the Early Chalcolithic.

Paleogeneticists sequenced the children's genomes at low depth and determined that they were two girls. Despite their remains being buried under the floor of the same dwelling, DNA analysis revealed that they were not closely related—at least, cousins or closer. Researchers had previously noted this when analyzing the genomes of the East Hill people.

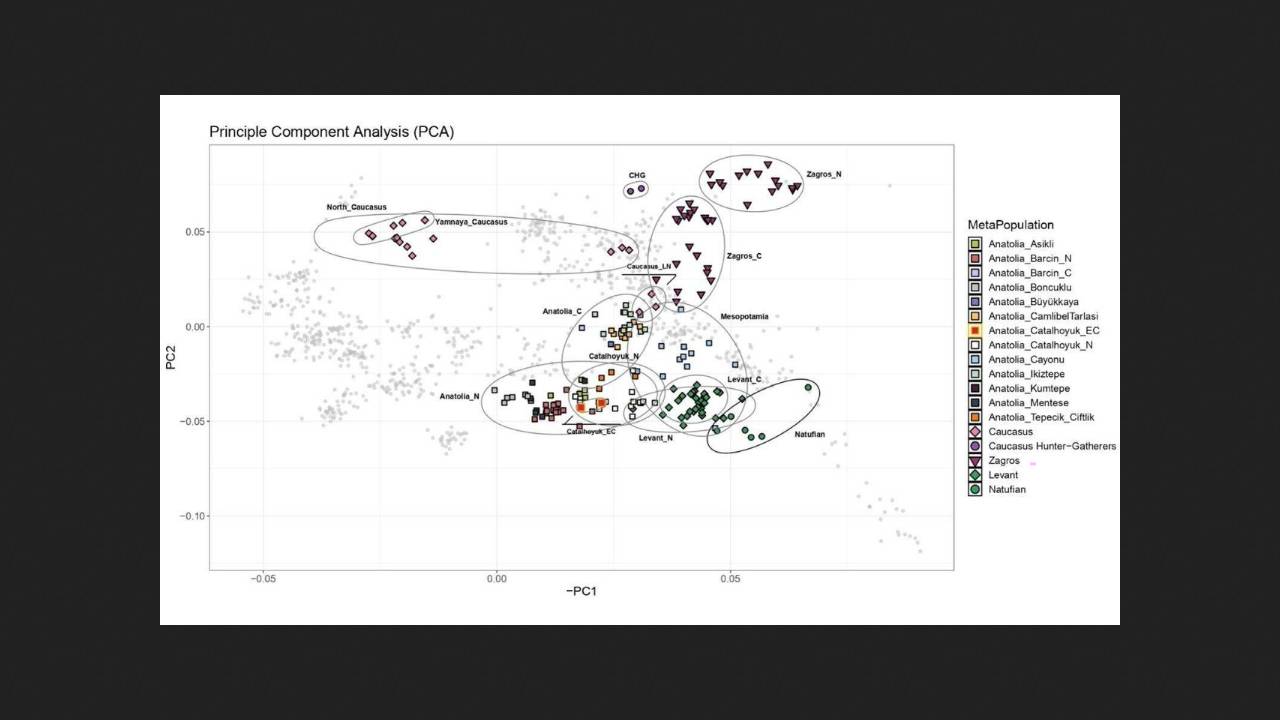

Previous studies have shown that the gene pool of the Central Anatolian population underwent significant changes in the sixth millennium BCE. At this time, gene flow occurred from more eastern populations, likely living in the Caucasus, Upper Mesopotamia, or Zagros. However, the genomes of children from the Western Hill of Çatalhöyük lacked this "eastern" admixture and were similar to the genomes of people from the Eastern Hill, who lived during the Neolithic era. Scientists believe that either gene flow from eastern populations reached Central Anatolia after these children were alive, or the Çatalhöyük population remained isolated. Other genomes from the early sixth millennium from this region may provide an answer to this question.

Research at Çatalhöyük continues, and scientists periodically report new discoveries. For example, earlier this year, we reported on the discovery of 8,600-year-old bread at this site, and last year, fragments of rope and textiles made from bast fibers.