British doctors delivered a functional gene to one eye of children with hereditary retinal dystrophy and significantly improved their vision. Before treatment, the patients could only detect light, but 3.5 years after therapy, they were able to perform simple visual tasks. A paper describing the study was published in The Lancet.

Hereditary retinal dystrophies lead to blindness in children from birth. There are 26 known genes whose defects can cause vision impairment. Currently, treatment only exists for RPE65-associated dystrophy: an adenoviral vector containing DNA with the active gene for the RPE65 enzyme, which "turns on" the eye's light-sensitive cells, is delivered to the eye.

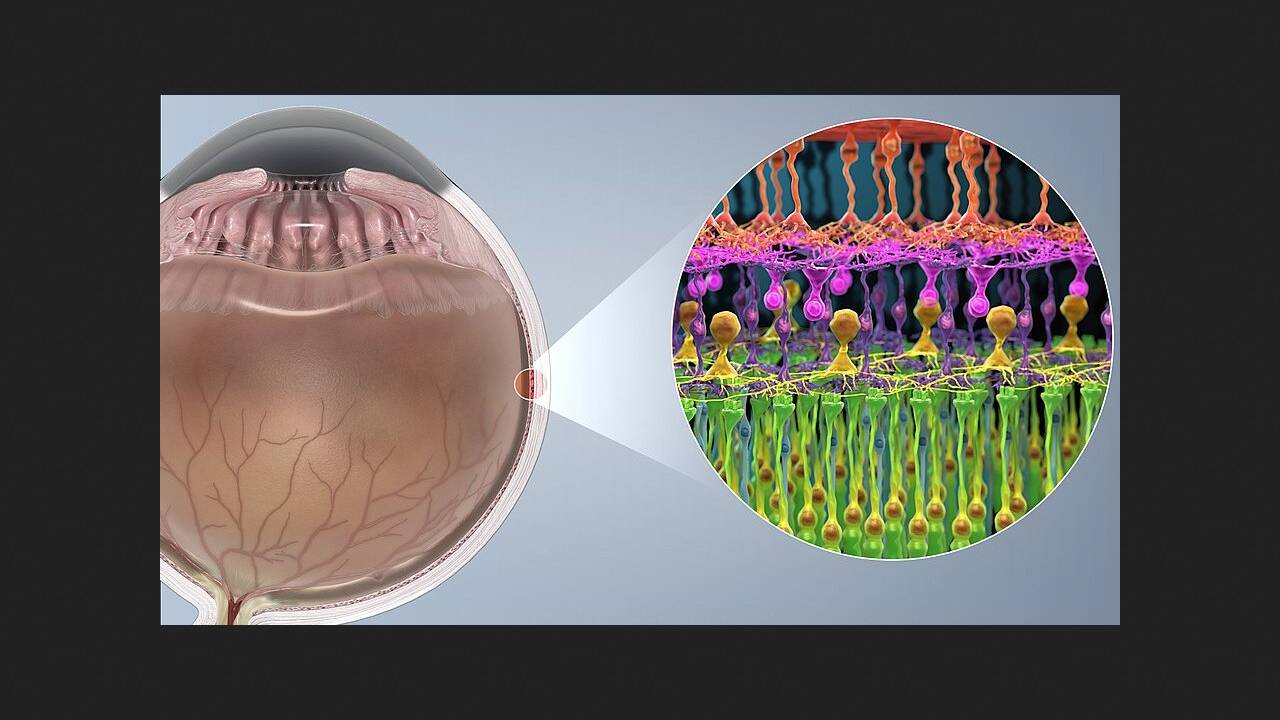

The AIPL1 gene encodes a protein necessary for phototransduction. It is expressed in rods and cones during embryonic development. In children with an AIPL1 defect, the rods and cones malfunction and gradually die off, causing them to be born virtually blind and typically only able to detect light.

Researchers led by James W. B. Bainbridge of King's College London selected four children (aged 1–2.8 years) from 42 individuals with a defect in the AIPL1 gene who had relatively intact fovea. This fovea contains a large concentration of photoreceptors, which increases the likelihood of gene therapy success.

Scientists created a vector based on an adeno-associated virus encoding the AIPL1 sequence. The drug was delivered to one of the patients' eyes via a subretinal injection. To assess the therapy's effectiveness, children were given simple tasks, such as placing pencils in a cup or picking up objects from the floor.

Three and a half years after treatment, the children's vision in the eye receiving the treatment improved significantly—they were able to perform simple visual tests. By the time of the follow-up examination, vision in the untreated eye had been completely lost.

Scientists hope to make the treatment available to more patients in the future, given the impressive results and lack of serious side effects.

In addition to hereditary retinopathies, gene therapy is also used to treat a hereditary disorder of the ganglion cells of the retina and optic nerve—Leber optic neuropathy.