German scientists analyzed the skeleton of an adult human discovered many years ago during excavations of a prestigious central burial site within one of the Hallstatt culture burial mounds, erected in the first millennium BC near the large ancient Celtic settlement of Heuneburg. The researchers discovered that the remains likely belonged to a man who had been shot in the pelvis by an arrow, traces of which are visible on the ischium. Despite the severe injury, the man survived, most likely due to medical attention and care. The article was published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology.

In Baden-Württemberg, Germany, lies the Heuneburg archaeological site—a very large settlement of the Hallstatt culture, which in Central Europe is primarily associated with the ancient Celts. In the vicinity of Heuneburg, often considered the first city north of the Alps, which existed in the second half to mid-first millennium BC, archaeologists have discovered, among other things, a number of ancient burial mounds containing high-status burials dating back to the Iron Age.

One of the small groups of burial mounds investigated near Heuneburg is called Gießübel-Talhau. Three of the four mounds in this group were excavated in the last quarter of the 19th century, and another in the second half of the 20th. The latter originally represented a large structure, the diameter of whose mound reached approximately 42.5–45 meters. Within this mound, archaeologists discovered a central burial, plundered in ancient times, surrounded by more than two dozen lesser burials.

Michael Francken of the Office for the Protection of Monuments in Konstanz and his colleagues from the University of Tübingen devoted an article to the central burial of this mound. In addition to fragments of a cart, horse harness, jewelry, and several other artifacts preserved in the grave by robbers, the researchers discovered the remains of an adult who, in all likelihood, enjoyed high social status in life and was buried with honors around 530–520 BC.

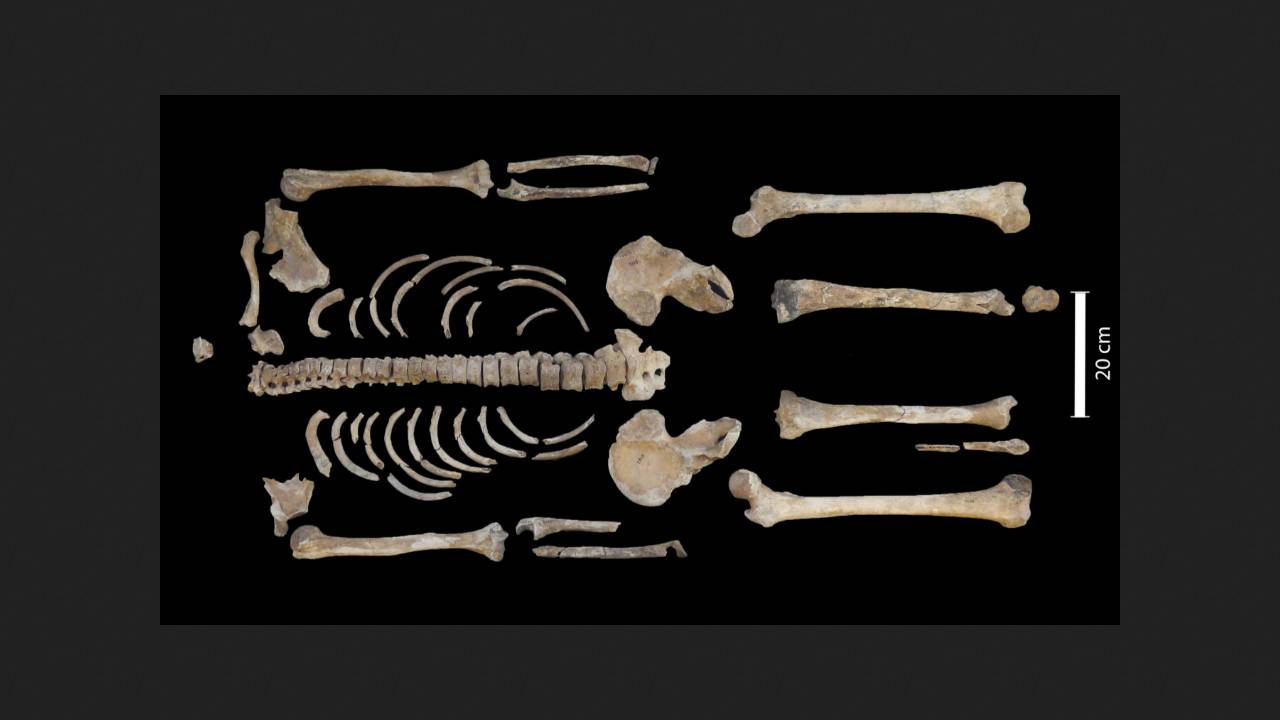

Scientists settled on an analysis of a human skeleton, the skull of which is currently considered lost, but the skeleton was otherwise quite well preserved. Anthropologists determined that the remains from this burial belonged to a single adult male who lived between 30 and 50 years. In life, his height reached approximately 169–172 centimeters, which, according to the researchers, is approximately seven to eight centimeters taller than the average height of Iron Age men from Central Europe. This confirms previous observations that the elite of early Celts from high-status burials were taller than the average population.

Scientists discovered a lesion on the man's left ischium, the result of a penetrating wound. Apparently, someone had fired an arrow from a bow, which entered his body in the pelvic area from the ventral side. Despite the severity of this wound, the man survived, as evidenced by signs of healing on the bone. The embedded metal arrowhead, which was quite possibly diamond-shaped, was likely removed from the body, and the man himself received medical attention and care, which allowed him to survive. He was likely lucky that the arrow did not sever any major blood vessels and, apparently, did not damage any nerves, injury to which could have led to impaired motor function in his legs—at least, his bones show no signs of atrophy.

N+1 previously reported on how paleogeneticists analyzed the DNA of members of the ancient Celtic elite, whose burials were excavated in southwestern Germany. The scientists concluded that these people likely traced their descent and inheritance through the maternal line.