Paleogeneticists have analyzed the DNA of a man whose remains were found almost a century ago in a prestigious tomb in the ancient city of Ephesus. Scientists have refuted the hypothesis that they could have belonged to Arsinoe IV, the sister of the famous Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII. A genomic study revealed that the tomb actually contained the remains of a teenage boy. This was reported in a paper published in the journal Scientific Reports.

In 1904, archaeologists discovered a prestigious monumental tomb, commonly known as the Octagon, in the central part of ancient Ephesus. A quarter of a century later, researchers opened the burial chamber of this structure and found a marble sarcophagus containing the remains of a single individual. The tomb contained no inscriptions or artifacts indicating the identity or social status of the deceased, but judging by its design and location, it was built for a person of high status.

The deceased's skull was then taken to Europe, where researchers subsequently concluded that it may have belonged to a young woman, approximately 20 years old at the time of her death (later estimates range from 15 to 17 years old). Decades later, a hypothesis arose that the tomb may have contained the remains of Arsinoe IV, the sister of the famous queen Cleopatra VII, who waged a power struggle in Egypt in the mid-first century BC. Arsinoe was initially captured by Julius Caesar, who took pity on her and allowed her to escape from Rome to Ephesus, where several years later, in 41 BC, she was assassinated on the orders of Mark Antony.

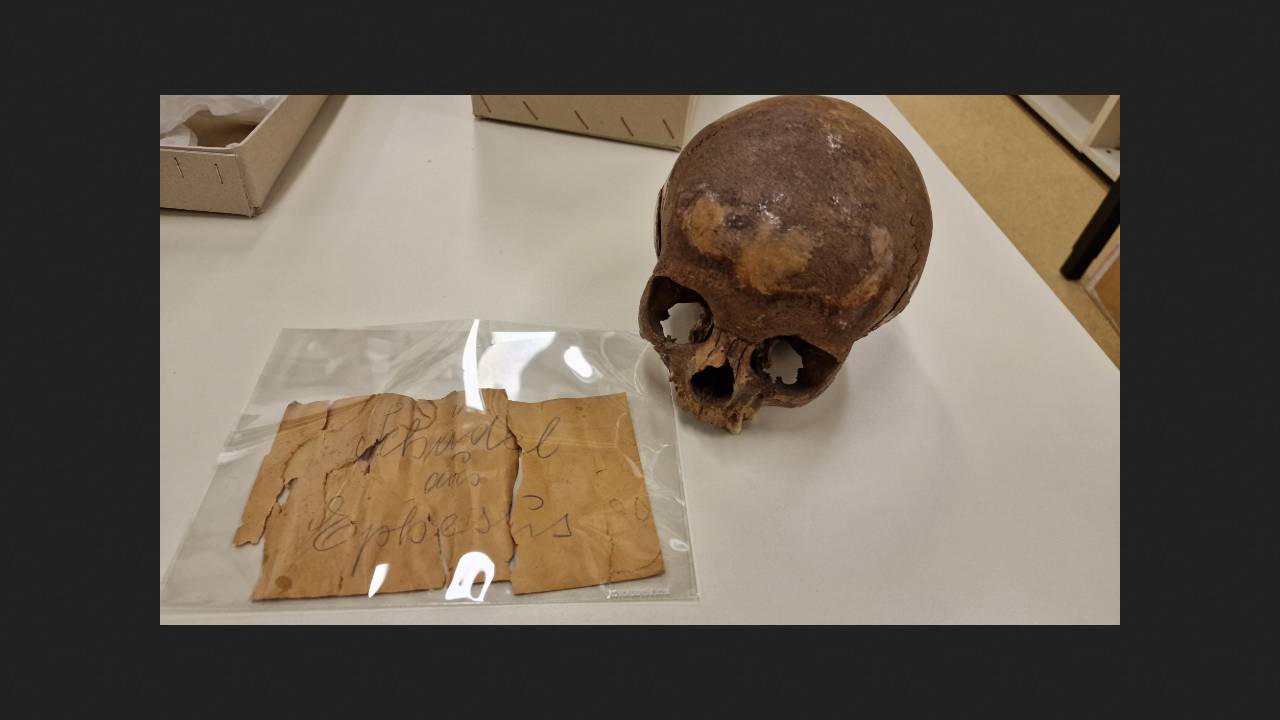

Gerhard Weber and his colleagues from the University of Vienna returned to the study of the Ephesus skull, recently rediscovered in Vienna's vaults. The study also included a femur and a rib found during a reopening of the Ephesus tomb several decades ago. However, the scientists were not certain that these bones belonged to the same individual as the skull.

Anthropologists determined that the skull belonged to an adolescent with abnormal development of the cranial bones (particularly the maxilla), who died between the ages of 11 and 14, much younger than expected for Arsinoe. To determine the age of this individual, scientists turned to radiocarbon dating. Initially, the researchers obtained a calibrated date of 355–170 BCE. However, after adjusting for the likely reservoir effect, they concluded that the child died between 205 and 36 BCE. Scientists had previously obtained a similar date for a femur from this tomb: 210–20 BCE.

Paleogeneticists then isolated ancient DNA from the skull, femur, and rib to determine whether the remains belonged to the same individual, their gender, and their origin. Genomic analysis revealed that the analyzed samples could not belong to Arsinoe IV, as both the skull and femur (possibly the rib as well, but the quality of the DNA extracted from this element was poor) belonged to a male. Furthermore, the skull and femur likely belonged to the same individual (or twins). As with sex determination, the conclusions regarding whether the rib belonged to the same individual remained quite uncertain.

Further genomic analysis revealed that the adolescent boy whose burial was excavated in Ephesus apparently had no significant North African ancestry. Instead, his ancestors were genetically similar to people who lived in southern Europe during the Bronze and Iron Ages. The boy was genetically closest to populations that lived on the Italian Peninsula and Sardinia around 500 BC.

Geneticists recently completed an analysis of the remains of a supposed Pompeian woman who died during the eruption of Vesuvius in the House of the Golden Bracelet. DNA analysis revealed that this individual was, in fact, a dark-skinned man.